Understanding RPCs - Part I

Having looked at a distributed system i.e the domain name system in the previous post, lets turn our attention to something more fundamental. In this blog post, we are going to start diving deeper into one of the basic blocks of Distributed Systems - Remote Procedure Calls or RPCs.

The paper that we’re going to be looking at today is authored by the duo of Nelson and Birell who were the first set of people to build an RPC implementation for their work at Xerox PARC. Nelson incidentally is also credited for the coining the term!

Why RPCs?

In the last post, we defined a distributed system as below -

A distributed system is a set of independent machines that coordinate over a network to achieve a common goal.

One of the important keywords in the above definition is coordinate. However, in order to coordinate, systems first need a way to communicate. Given that we have a messaging layer (the network) what kind of a communication abstraction we can build that can be helpful to programmers while building distributed systems?

RPCs are one such abstraction borrowed from programming languages that have a simple goal:

Make the process of executing code on a remote machine as simple and straight-forward as calling a local function.

But why did we specifically choose procedures? Let’s hear what the authors have to say - RPCs are based on the observation that procedure calls are a well known and well understood mechanism for transfer of control and data within a program running on a single computer. Therefore, it is proposed that this same mechanism be extended to provide for transfer of control and data across a communication network.

Components

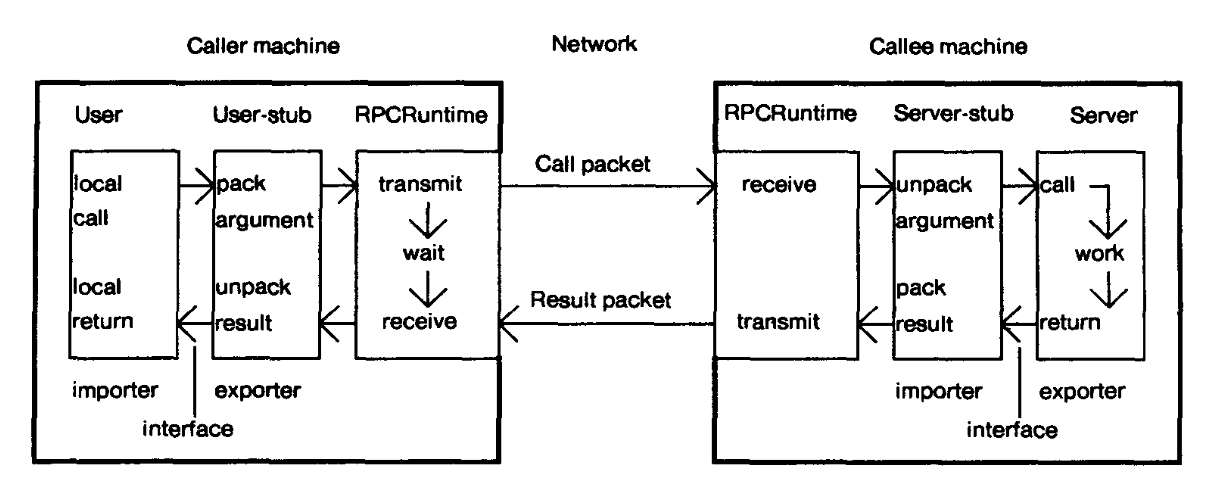

The underlying mechanism of a RPC is simple - the caller machine makes a procedure call over a network to the callee machine which then executes the procedure locally, collects the results and sends it over to the caller. The figure above lays out the key components in an RPC system, which at a high-level has two main pieces: a stub generator and the run-time library.

The stubs are responsible for placing a specification and packing / unpacking the arguments falling that specification into the message. This message is then forwarded to the runtime so that it can be wired to the callee (in case of the user-stub). The process of packing the arguments is usually called marshalling or serialization of the message. Likewise, unmarshalling or deserialization involves extracting information received into something which the system can understand.

When writing a distributed application, a programmer first writes an interface module in which she specifies the procedure names, the types of the arguments it takes and finally the return types. The compiler then uses this definition and generates the user-stub and the client-stub.

// An example of an interface for generating stubs

service FacebookService {

// Returns a descriptive name of the service

string getName(),

// Returns the version of the service

string getVersion(),

// Gets an option

string getOption(1: string key),

// Gets all options

map<string, string> getOptions()

}

The runtime is responsible for retransmissions, acknowledgments, packet routing, and encryption. It handles much of the heavy lifting in the RPC system. One of the key challenges faced by the runtime is locating the remote service. Once the service is located, the RPC package then binds the importer of the interface to an exporter of the interface.

Naming

The problem of naming is a common one in distributed systems. In a cluster how do we know the names and addresses of each of the machines? How do we maintain this list and do we keep this dynamic? We’ll look at these problems much later when we talk about directory services and service discovery.

In the paper the authors use Grapevine, a distributed service that provides DNS service, resource locating service, authentication and mail service.

The major attraction of using Grapevine is that it is widely and reliably available. Grapevine is distributed across multiple servers strategically located in our internet topology, and is configured to maintain at least three copies of each database entry. Since the Grapevine servers themselves are highly reliable and the data is replicated, it is extremely rare for us to be unable to look up a database entry.

For more info, checkout the paper on Grapevine.

Protocol

Once the caller knows which callee it needs to communicate with, the next question is which transport level protocol to use? The authors had an option of going ahead with a PUP byte stream protocol but decided against it as the protocol was ideal for sending bigger data packets. In the case of RPC, the design goal was different -

One aim we emphasized in our protocol design was minimizing the elapsed real-time between initiating a call and getting results. With protocols for bulk data transfer this is not important: most of the time is spent actually transferring the data.

In the modern world, we have an option of using UDP (an unreliable protocol) or TCP (a reliable protocol). While the choice might seem clear, the caveat here is that building RPC on top of a reliable communication protocol can lead to a severe drop in performance. Hence, many RPC packages are built on top of unreliable communication layers (e.g. UDP) and then bake in the extra logic for dealing with ACKs, retries etc.

Now would be a good time to talk about Thrift - the RPC framework developed at Facebook. Thrift has its own interface language called IDL that is used to generate the stubs. The communication protocol uses protocol buffers as its data format under the hood. Unlike XML/JSON protocol buffers are a binary format and hence is much smaller, less ambiguous and faster than a plain-text data format.

Apache Thrift allows you to define data types and service interfaces in a simple definition file. Taking that file as input, the compiler generates code to be used to easily build RPC clients and servers that communicate seamlessly across programming languages.

Nowadays Thrift is being used more and more amongst heterogenous services to talk amongst each other - for example, you could write a user authentication service in Java, but call it from your Ruby web application.

Conclusion

In this post we went over the overall idea behind RPCs and took a deep dive into the components which form a RPC system. In the next post we are going to continue our discussion about RPCs by talking about semantics and some limitations of RPCs.