The SWIM Membership Protocol

Let’s say that you asked to build a distributed database similar to Cassandra. Your storage system will store and process large amounts of data running on a huge number of commodity servers. In other words, your system will rely on the power of 100s of nodes to manage data.

At this scale, failures will be the norm rather than the exception. Even if we assume that one node lasts for 1000 days (roughly 3 years), in a cluster of 500 nodes there will be a failure once every 2 days.

To deal with this scenario, you would require a failure detection service, which apart from detecting faulty nodes also keeps all non-faulty processes in sync about the processes that are alive. In this blog post, we’ll cover one such protocol called SWIM and understand its inner workings.

SWIM

The SWIM or the Scalable Weakly-consistent Infection-style process group Membership protocol is a protocol used for maintaining membership amongst processes in a distributed system.

A membership protocol provides each process of the group with a locally maintained list, called a membership list, of other non-faulty processes in the group.

The protocol, hence, carries out two important tasks -

- detecting failures i.e. how to identify which process has failed and

- disseminating information i.e. how to notify other processes in the system about these failures.

It goes without saying that a membership protocol should be scalable, reliable and fast in detecting failures. The scalability and efficiency of membership protocols is primarily determined by the following properties

- Completeness: Does every failed process eventually get detected?

- Speed of failure detection: What is the average time interval between a failure and its detection by a non-faulty process?

- Accuracy: How often are processes classified as failed, actually non-faulty (called the false positive rate)?

- Message Load: How much network load is generated per node and is it equally distributed?

Ideally, one would want a protocol that is strongly complete 100% accurate which means that every faulty process is detected, with no false positives. However, like other trade-offs in distributed systems there exists an impossibility result which states that 100% completeness and accuracy cannot be guaranteed over an asynchronous network. Hence, most membership protocols (including SWIM) trade in accuracy for completeness and try to keep the false positive rate as low as possible.

SWIM Failure Detector

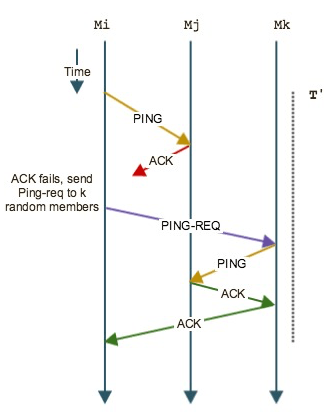

The SWIM failure detector uses two parameters - a protocol period T and an integer k which is the size of failure detection sub-groups.

The figure above shows how the protocol works. After every T time units, a process Mi selects a random process from its membership list - say Mj - and sends a ping to it. It then waits from an ack from Mj. If it does not receive the ack within the pre-specified timeout, Mi indirectly probes Mj by randomly selecting k targets and uses them to send a ping to Mj. Each of these k targets then sends a ping to Mj on behalf of Mi and on receiving an ack notifies Mi. If, for some reason, none of these processes receive an ack, Mi declares Mj as failed and hands off the update to the dissemination component (discussed below).

The key differentiating factor between SWIM and other heart-beating / gossip protocols is how SWIM uses other targets to reach Mj so as to avoid any congestion on the network path between Mi and Mj.

SWIM Dissemination Component

The dissemination component simply multicasts failure updates to the rest of the group. All members receiving this message delete Mj from its local membership list. Information about new members or voluntarily leaving is multicast members in a similar manner. Information about newly joined members or voluntarily leaving members are multicast in a similar manner.

Improvements

Infection-Style Dissemination - In a more robust version of SWIM, instead of relying on the unreliable and inefficient multicast, the dissemination component piggybacks membership updates on the ping and ack messages sent by the failure detector protocol. This approach is called the infection-style (as this is similar to the spread of gossip, or epidemic in a population) of dissemination which has the benefits of lower packet loss and better latency.

Suspicion Mechanism - Even though the SWIM protocol guards against the scenario where there’s congestion between two nodes by pinging k nodes, there is still a possibility where a perfectly healthy process Mj becomes slow (high load) or becomes temporarily unavailable due to a network partition around itself and hence is marked failed by the protocol.

SWIM mitigates this by running a subprotocol called the Suspicion subprotocol whenever a failure is detected by the basic SWIM. In this protocol, when Mi finds Mj to be non-responsive (directly and indirectly) it marks Mj as a suspect instead of marking it as failed. It then uses the dissemination component to send this message Mj: suspect to other nodes (infection-style). Any process that later finds Mj responding to ping un-marks the suspicion and infects the system with the Mj: alive message.

Time-bounded Completeness - The basic SWIM protocol detects failures in an average constant number of protocol periods. While every faulty process is guaranteed to be detected eventually, there is a small probability that due to the random selection of target nodes there might be a considerable delay before a ping is sent to faulty node.

A simple improvement suggested by SWIM to mitigate this is by maintaining an array of known members and selecting ping targets in a round-robin fashion. After the array is completely traversed, it is randomly shuffled and the process continues. This provides a finite upper bound on the time units between successive selections of the same target.

CONCLUSION

The SWIM protocol has found its use in many distributed systems. One popular open-source system that uses SWIM is Serf, which is a decentralized solution for cluster membership by Hashicorp. The documentation has a reasonably clear walkthrough of the underlying architecture. The good people at Hashicorp have also open-sourced their implementation on Github. For the ones who understand better by reading code, be sure to check that out.

Lastly, this blog post deliberately keeps out the math to make the high-level ideas simple, but if you’re interested in diving deeper be sure to read the paper to better understand upper bounds on false positive rate, average time for detecting failures and network load.

I hope this blog post gave you a glimpse into how SWIM, a popular membership protocol works. If you have questions, do let me know in the comments below.